By declaring that Italy’s official gold reserves – the third largest in the world – belong to the “Italian people”, the government of Giorgia Meloni is essentially highlighting the emergency plan it has for a major crisis, one it in fact considers imminent.

At a time of declining trust in European institutions, this is the last thing the Eurozone needs.

The Italian government proposed an amendment to the 2026 budget law, according to which the gold held by the Bank of Italy “belongs to the Italian people” and not to the “state”.

The wording may appear innocuous – who would argue otherwise? – however it has triggered a wave of speculation, as well as calls from the European Central Bank for the provision to be withdrawn.

Legally, the amendment has no substantive content, for now.

The ownership and management of the gold reserves on the balance sheet of the Italian central bank are already precisely defined.

The Bank of Italy is fully integrated into the European System of Central Banks (Eurosystem), which is governed by the Treaties of the European Union, the Statute of the Eurosystem, and Italian law.

These frameworks ensure, on the one hand, the operational independence of the central banks of the member states and, on the other, prevent national governments from appropriating national reserves.

In other words, with or without the new amendment, Italy would not be able to use its gold reserves to finance public spending or reduce its debt without the consent of the ECB, something that would not happen anyway.

However, in the evolving institutional framework of the Eurozone, symbolic moves carry political weight.

Alignment with Donald Trump and the patriotic message

The ruling party in Italy appears increasingly aligned with the worldview espoused by the administration of US President Donald Trump, as reflected in the latest National Security Strategy (NSS), which portrays the EU as a scourge on “political freedom and national sovereignty”.

By stating that gold “belongs to the people”, the Italian government sends a message to voters who view the euro as an externally imposed constraint and the ECB as insufficiently accountable: the EU does not belong to us, and the nation still comes first.

This message certainly resonates.

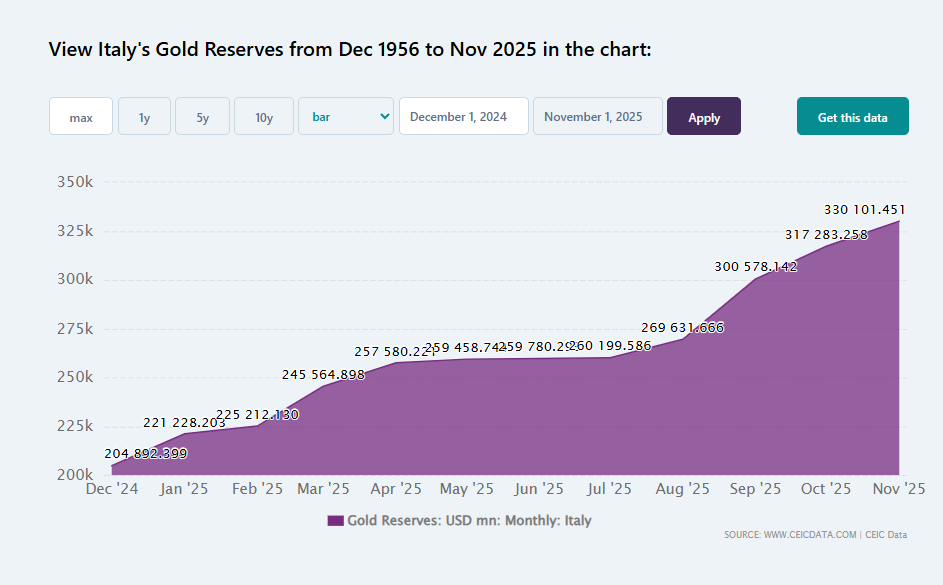

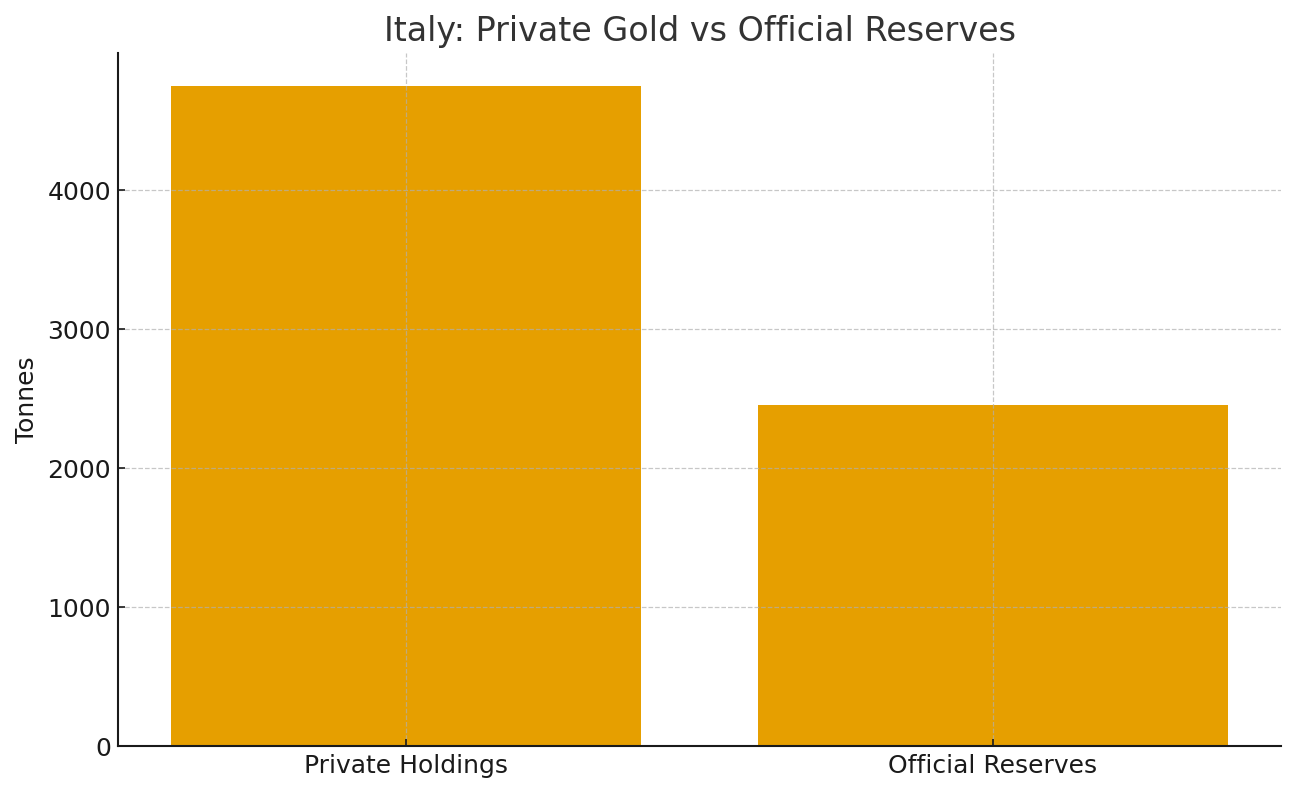

Italy has long characterized its substantial gold reserves – the third largest in the world, totaling 2.452 metric tons – as a kind of reserve with regard to economic sovereignty.

For a state that has long struggled for fiscal health, the idea that a hidden asset can guarantee autonomy and independence in times of crisis is politically powerful.

As long as Italy remains a member of the Eurozone, this logic clashes with the reality of how European institutions function.

Every time Italian politicians have proposed using gold to reduce debt or support the economy, they have run up against constraints arising from the treaties.

Awaiting the disintegration of the EU

If, however, Italy were to leave the Eurozone, either on its own or as part of a broader disintegration, the country’s gold reserves would anchor a new national currency, serve as a guarantee for stabilizing financial markets, and be transformed into a symbol of restored economic sovereignty.

Perhaps this is the aim of the amendment to the budget law: to hint at a future in which gold could function as a pillar of Italian economic sovereignty – still an extremely remote possibility – without provoking an institutional confrontation.

But why hint, even faintly, at such a future? And why now?

Three possible explanations stand out.

1) The first explanation is that the amendment constitutes an internal political maneuver. Italy’s governing coalition, led by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, includes parties with long standing eurosceptic tendencies. As Italy enters a period of tense negotiations over fiscal rules, budget targets, and access to EU funds, an appeal to national sovereignty is a cost free way to relieve internal pressure without altering the country’s policy commitments.

2) Second, the amendment may aim to send a subtle message to European officials. Italy remains a large and systemically important member of the Eurozone, and its economic stability is inextricably linked to that of the monetary union. By highlighting its significant gold reserves, the government may be seeking to remind EU institutions and the ECB that fiscal negotiations must take political realities into account. In a system based on mutual trust, symbolic moves can function as a form of negotiation.

3) Finally, Italy may be insulating itself against a rapidly changing geopolitical environment. Meloni has adopted a noticeably warmer stance toward Trump compared to most European leaders, who bristle at his lack of commitment to the transatlantic alliance and his coordinated efforts to heighten Europe’s strategic uncertainty. With the amendment to the budget law, Meloni may be seeking to ensure that her party is regarded as one of the “patriotic European parties” whose “growing influence” is highlighted by the NSS of the Trump administration. None of this explicitly means that Italy plans to exit the euro, at least for now, but that it is preparing for a Great Reset.

Preparation for the impending crisis

By underscoring the “ownership of the people” over Italy’s gold reserves, the government is essentially highlighting the emergency plan it has for a major crisis, particularly for an exit from the Eurozone or its dissolution.

In a period of weak growth, geopolitical turbulence, strategic uncertainty, and declining trust in European institutions, it is significant that centrifugal tendencies are taking shape.

After all, a monetary union is held together by political commitments as much as by legal frameworks. Questioning those commitments, even subtly, can shake its foundations.

Italy’s gold remains safely stored in the vaults of its central bank.

But Europe can no longer ignore narratives that can generate significant uncertainty as to whether it will remain there and the demand for economic sovereignty.

www.bankingnews.gr

Σχόλια αναγνωστών