The Peace Council is presented as an ambitious alternative peace architecture—yet a lack of institutional grounding, hyper-concentration of power, and limited international acceptance create grave risks

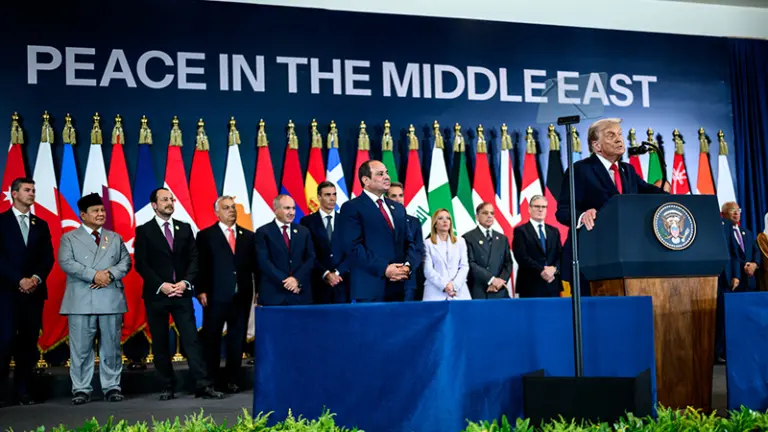

The curtain fell on February 19, 2026, in Washington for the so-called Peace Council, a new initiative that, according to US President Donald Trump, will be "the largest and most important... ever assembled." This declaration captures the sheer scale of American leadership's ambitions. However, behind the rhetoric of power, serious questions are emerging regarding the legitimacy, functionality, and geopolitical consequences of such a structure.

Initially, the Peace Council was reportedly designed to address the crisis in Gaza. However, its new Charter goes far beyond this scope, criticizing "failed institutions" and proclaiming an intent to "promote stability, restore lawful governance, and ensure lasting peace in regions affected or threatened by conflict." This reference is widely interpreted as a jab at the UN, which Washington—particularly under Trump—views as a bloated bureaucracy riddled with ideological distortions.

Excessive ambitions and the risk of resource dissipation

The fundamental problem is not merely political but strategic. The Peace Council seems to claim a role extending beyond Gaza, touching on crises like the Egypt–Ethiopia dispute, or even assuming the responsibilities of dozens of international organizations from which the US withdrew in 2026. Trump’s statement that the body can "do almost whatever its members want" suggests a framework without clear boundaries of jurisdiction.

This creates the risk of geopolitical overextension. American foreign policy may be dissipated across multiple fronts not directly related to vital national interests. Instead of resource concentration and strategic clarity, the Council may lead to disorientation and a heavy burden on American power.

Institutional deficits and lack of legitimacy

Despite promises of "flexible and effective" procedures, the Peace Council lacks basic mechanisms for enforcement, dispute resolution, and accountability. It possesses no structure to ensure good governance or mechanisms for the check of power.

The hyper-personalization of the institution is also problematic. Trump reportedly controls:

-

Membership invitations

-

The body's finances

-

The daily agenda

-

Veto rights

-

Member expulsion

He can only be replaced if he resigns or is unanimously deemed incapacitated, while only he can appoint a new chairman. This concentration of power undermines the image of impartiality and transforms a multilateral format into a semi-presidential policy tool.

Controversial personal choices

The proposal to assign executive roles to figures such as former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, co-architect of the Iraq War, or Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who faces an investigation by the International Criminal Court, raises further questions of credibility. Instead of bolstering trust, such a composition may intensify suspicions that the Board operates as a political tool for selective influence rather than a neutral mediator.

Bypassing international principles

In contrast to post-war principles of international law—national sovereignty, self-determination, and the equality of states—the Council appears to bypass or downgrade them. The absence of these principles from the Charter may reinforce the perception that this is a "bespoke" mechanism for Washington. Meanwhile, the financial requirement for participation—$1 billion after three years—limits the ability of less developed nations to join. The result is a selective club with limited representativeness.

Limited international acceptance – Russia, China, India stay out

Despite acceptance from countries like Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Indonesia, and Israel, approximately 40 of the 60 invited nations have not joined. China, Russia, and India maintain a cautious stance, while many European democracies keep their distance, concerned about the relationship with the UN and potential Moscow participation. Even the Sunni Arab states that accepted the invitation reportedly did so primarily for the resolution of the Gaza crisis, not for a total geopolitical realignment.

Potential impact on American interests

Hostility toward the UN could accelerate its institutional and economic weakening. However, despite its problems, the UN has played a stabilizing role in regions at a relatively low cost to the US. Further weakening it may lead to regional destabilizations requiring more expensive and direct American interventions. In the case of Gaza, the unequal representation of Palestinians relative to Israel could undermine the next phase of the peace process—a phase involving disarmament, reconstruction, and a potential International Stabilization Force under US supervision.

Serious risks

The Peace Council is presented as an ambitious alternative peace architecture. However, the lack of an institutional base, the hyper-concentration of power, controversial personnel choices, and limited international acceptance create serious risks. Instead of strengthening American influence, it may erode it, pushing other states into alternative alliances that bypass Washington.

The effective management of the Gaza crisis would require institutional legitimacy, balanced representation, and respect for international principles—not a mechanism that risks being perceived as a unilateral tool of power. If Washington truly seeks lasting peace, it will need to temper the Council’s excessive ambitions and reposition the initiative within a cooperative framework that combines realism, legitimacy, and sustainability.

www.bankingnews.gr

Σχόλια αναγνωστών